Category: Architecture

Bodys Isek Kingelez: City Dreams

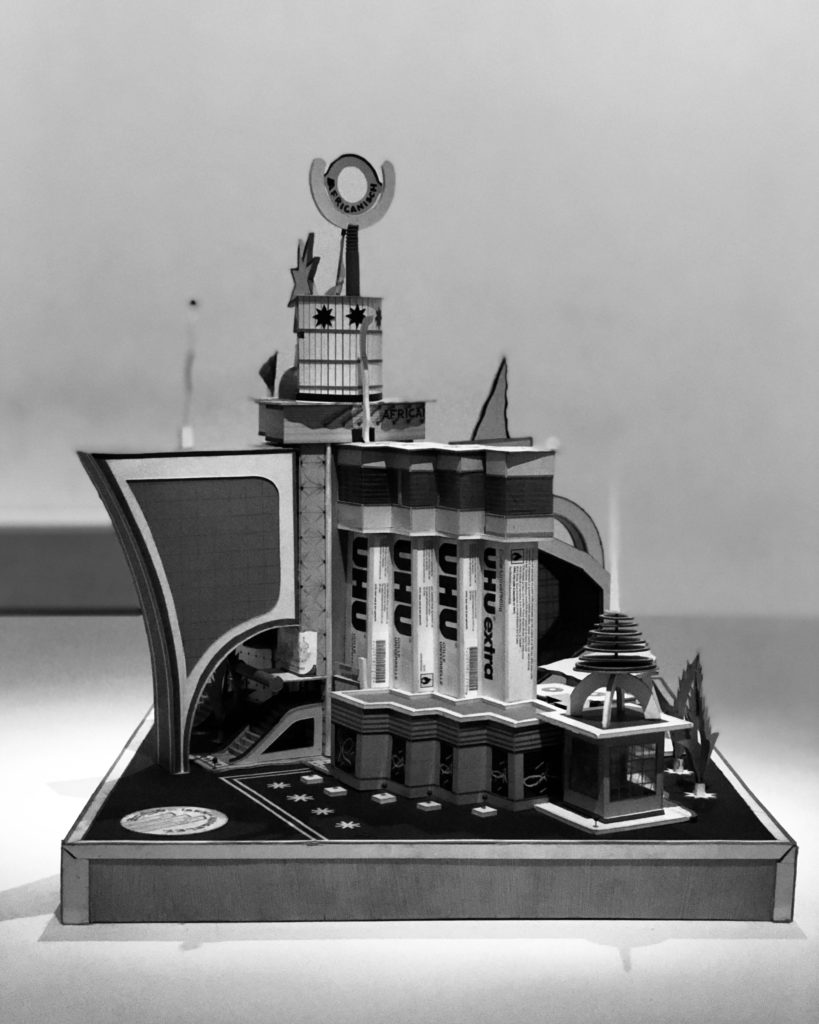

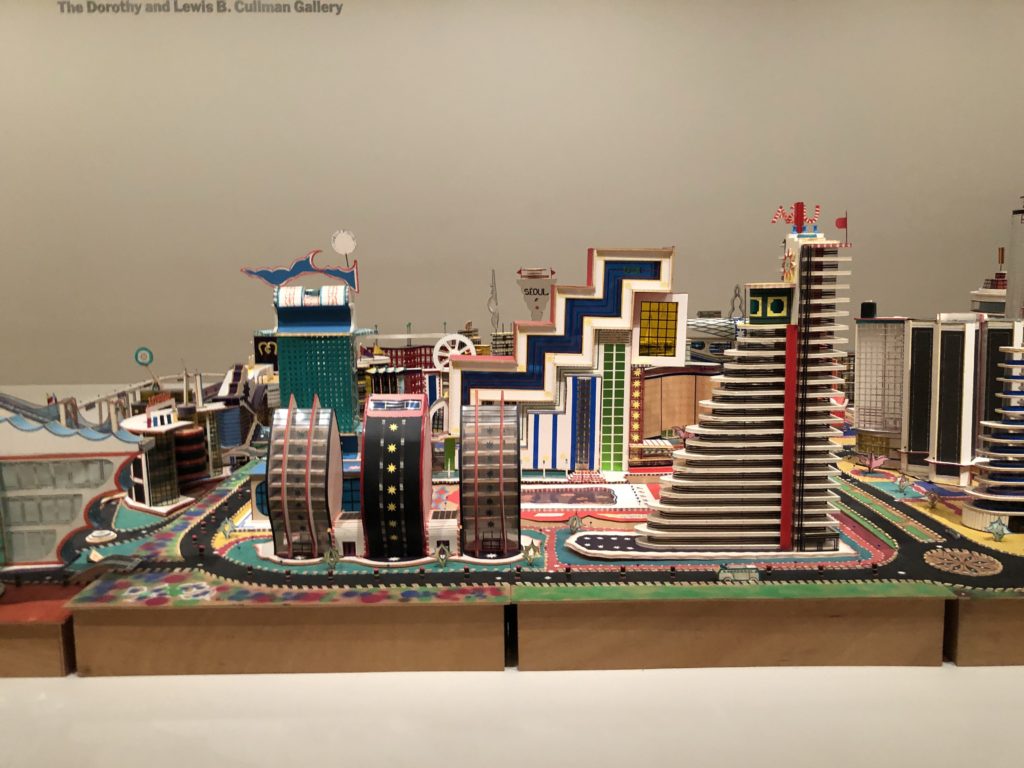

At MoMA, through the rest of 2018, is an interesting exhibition entitled Bodys Isek Kingelez: City Dreams. It is a retrospective of artist Bodys Isek Kingelez (1948–2015) who was based in then-Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo):

following its independence from Belgium, Kingelez made sculptures of imagined buildings and cities that reflected dreams for his country, his continent, and the world.

These are amazing models of what could happen, a speculative dream for a new country emerging from great change, all created from everyday and readymade objects. The work is amazing, and you should go. A few times.

My criticism of the work is that the future dreamworld looks dreadful from an urbanist point of view. The future that Bodys Isek Kingelez envisions has come to life in parts of Beijing and in Gurgaon, right outside New Delhi, India. Gurgaon is the manifestation of libertarian space; rife with walled fortress-like compounds which require a car to navigate from one to the other, all cloaked in dust and smog. There is no space for walking or biking; no space for simple pleasures of moving from space to space without the requirement of a car to convey you to that new space.

These are spaces where the body is cut off from each other; spaces where the building form is more important than the person:

Now this criticism might seem unfair, or jumping to conclusions based on art but the work as a whole leaves me with trepidation that the future dream is not truly human-centered, rather the future envisioned is a series of unconnected edifices. Yet this work also, in a way, correctly predicts star architects, run amok libertarian space, and the foregrounding of building not urbanism.

Case Study House – Wordless Wednesday

Salk Institute – Wordless Wednesday

Taking a slice out of life

Two quick examples showing a not-quite-yet trend of breaking down the physical world into slices. Is this part of The New Aesthetic or something different?

First off sheets of glass cut into layered ocean waves by Ben Young:

![]()

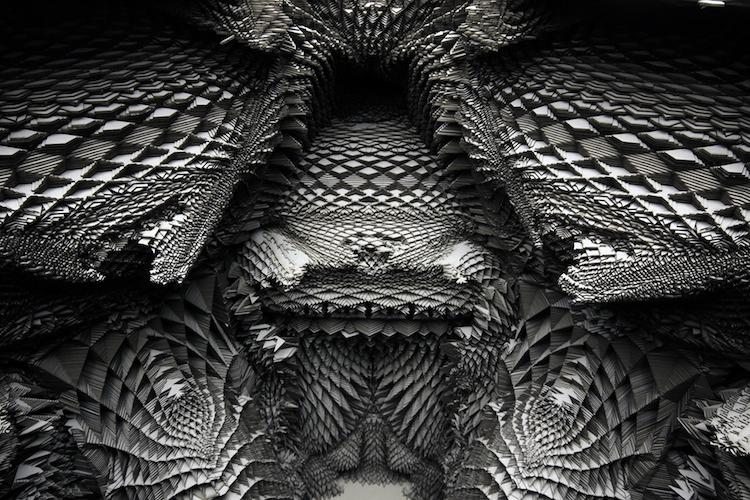

Second, the World’s Most Complex Architecture: Cardboard Columns With 16 Million Facets:

Hansmeyer’s column stands nine feet tall, weighs about 2000 pounds, and is made out of 2700 1mm-thin slices of cardboard stacked on top of wooden cores. It contains somewhere between 8 and 16 million polygonal faces — too complex for even a 3D printer to handle, according to Hansmeyer. “Every 3D printing facility we spoke to turned us down,” he tells Co.Design. “Typically those machines can’t process more than 500,000 faces — the computer memory required to process the data grows nonlinearly, and it also gets tripped up on the self-intersecting faces of the column.”

Paddington Station

Jackson Square

Canterbury Cathedral

The Competition

This trailer is almost too hard to watch, The Competition:

Jean Nouvel, Frank Gehry, Dominique Perrault, Zaha Hadid and Norman Foster are selected to participate in the design of the future National Museum of Art of Andorra, a first in the Pyrenees small country. Norman Foster drops out of the competition after a change in the rules that allow the documentary to happen. Three months of design work go into the making of the different proposals, while, behind doors, a power struggle between the different architects and the client has a profound impact on the level of transparency granted by each office to the resident documentary crew, and which has a definite influence in the material shown in the film.

Putting Hydraulic Jacks on the Farnsworth House

The continuing saga of the Farnsworth House brings us a new chapter. Preservationists are considering installing hydraulic jacks could protect Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House from flood danger:

Preservationists have proposed a system of hydraulic jacks that could safeguard Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House from flood damage by lifting it into the air.

The preferred choice, priced between £1.5 and £1.8 million, would involve temporarily moving the house from its site, then installing a system of hydraulic steel trusses and a pit from which floodwater could be pumped away.

“I think one of the risks is that this is a new application of an old technology,” said Meeks. “The risk is overcoming the question mark in people’s minds. People will want to be satisfied that it’s the simplest solution.”